REFORMERS IN INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT

Five Remarkable Lives

This book examines the fascinating life journeys of five exceptional individuals who overcame formidable barriers and challenges as they rose from humble beginnings in Africa, Latin America, and Asia to bring about far-reaching change and progress for millions of people burdened by poverty and lack of opportunity. Reflecting on the similarities and differences across the five – and the paths of development their nations experienced – the narrative draws out insights on leadership, decision-making, and how countries escape poverty.

Commenters on the book (examples below) have noted how it combines rigorous research, an analytical framework, and an appreciation for the eternal truth that few things appeal to – and persuade – readers more than a well-told story. The five stories in this volume delve into the character-revealing dilemmas these individuals faced, the tough choices they made, the values they held, the mistakes they made, and the strengths and flaws they learned to manage.

The book was written to be a resource for international development practitioners, scholars, and students, as well as a captivating introduction for readers completely unfamiliar with the development process that Africa, Latin America, and Asia are grappling with.

What are readers saying about

REFORMERS IN INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT: FIVE REMARKABLE LIVES

Chief Economist and Senior Vice President for Development Economics of the World Bank Group. Formerly at the Brookings Institution, Duke University, Georgetown University and the University of Chicago.

“There are thousands of books recommending development policies, but few on the policymakers implementing them. De Ferranti has written a wonderful book one about five of them: people with vision and ambition, facing a complex political environment, taking risks, committing mistakes but, in the end, making a positive difference.”

Brookings Institution. Former Chief Economist and Vice President for Sectors and Knowledge at the Inter-American Development Bank. Former Deputy Minister at the Ministry of Finance and Public Credit of Mexico. Former tenured Associate Professor of Economics at Boston University

“It is hard enough to convey the essence of one person’s character but David de Ferranti manages to achieve this for five remarkable people. Their lives, the achievements and the disappointments, hold valuable lessons for anyone interested in understanding what constitutes leadership in challenging times.”

President of the Center for Global Development. Formerly a Director at the International Monetary Fund. Former Director General, Policy and International at the UK government's Department for International Development (DFID)

“Combining page-turner verve with painstaking research, this engrossing exploration of the true stories of five remarkable individuals will captivate anyone, whether they know a lot or nothing about its subject matter — global development and the ways that Africa, Asia, and Latin America will change the world in the decades ahead. The wake-up call in its messages will keep you riveted.”

Former CEO of AFD, France's government agency for international development. Former senior official of the World Bank. Currently CEO of Investisseurs et Partenaires (I&P), Member of the National Academy of Technologies of France (Académie des Technologies), and Senior Fellow at FERDI (Foundation for Studies and Research on International Development)

“De Ferranti, after decades with a front row seat or in the driver’s seat in the field of international development, illustrates through the lives of five remarkable individuals one of the key drivers of change: learn as much as possible, go home, and do everything that is possible.”

Former President of Bolivia. Previously, acted as Vice-President and Finance Minister of Bolivia. Former Vice-President of The Club de Madrid.

“Individuals make a difference and can help improve the wellbeing of whole communities. This is the central message of this book. With eloquence and empathy, David de Ferranti describes the lives of five extraordinary characters who changed international development for the better. A must-read that is also fun to read.”

President of the University of Miami. Professor of public health science at the university's Leonard M. Miller School of Medicine, professor of health sector management at the university's Herbert Business School, and professor of sociology at its College of Arts of Sciences. Former Dean of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health at Harvard University. Former Secretary of Health in Mexico, the federal government cabinet post overseeing the country's health system and policies.

“David de Ferranti makes international development come alive through the captivating stories of five extraordinary global leaders, their personal journeys, struggles and victories intertwined with global and regional development. This book captures what it means to be an agent of locally driven democratic change. The author sums up the features of strong leadership, including wisdom, integrity and courage. I would recommend this book to any student of the politics, political economy and political science of international development.”

Senior Advisor, Global Public Health, Karolinska Institute. Former Director of the Global Financing Facility for Women and Children, The World Bank.

“This well-researched book will be a fascinating read for experts in the field as well as those who are relatively new to the international development challenges of African, Asian, and Latin American countries. The author, himself a recognized authority with inside knowledge, discusses difficult economic and sociopolitical issues in an engaging and readable way through his retelling of the lives of five remarkable individuals whom he has known well for decades.”

Director-General of Independent Evaluation at the Asian Development Bank. Former Executive Director and Chief Executive Officer of the International Initiative for Impact Evaluation. Former World Bank official. Managing Editor of The Journal of Development Effectiveness. Former faculty member of Economic Department of Western University in London, Canada

“In a book that profiles five remarkable leaders who have improved the lives and livelihoods of millions of people, David De Ferranti offers the gift of inspiration. The stories of these individuals sheds light on how each of us can rise to the challenges that confront us.”

Vice President of Just Societies and Chief Learning Officer at the David and Lucile Packard Foundation. Formerly held senior roles within IDInsight, The Hewlett Foundation, USAID, and The Center for Global Development

“Congratulations to the author of this book for offering an unusual and captivating set of stories about five remarkable individuals. Based on the author’s profound insider knowledge of their lives and minds, these accounts give fascinating views on their personal as well as professional features. This makes for a truly inspiring reading experience for anyone interested in human nature, including for the non-specialist of international development.”

Chairman of the Board of Investisseurs et Partenaires (I&P) and a former Director at the World Bank.

“This book on the trajectory of five remarkable leaders from Africa, Asia and Latin America is a wonderful and inspirational book to read. These five leaders were able to make great contributions to development in their countries thanks to their vision, clear priorities and ability to urgently implement audacious reforms and policies. As clearly highlighted by de Ferranti, their strong convictions, sense of opportunity, perseverance and ethical values are indeed a source of inspiration for future leaders worldwide.”

Former President of CAF Development Bank of Latin America, former Minister of Planning and Coordination and Head of the Economic and Social Cabinet of Bolivia, former Treasurer of the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB)

I originally picked up this book because I have had the pleasure of interacting personally with two of the five leaders profiled. I wanted to learn more about them. The book certainly delivered on that. But was surprised by how engrossing all five stories were. It was a page-turner!

The author effectively weaves together stories of professional achievements with personal information and anecdotes that bring out the humanity in each of these five leaders. And the reader comes away with a sense of what has driven these individuals, what they have overcome (a lot!), and what has made them successful. Taken as a whole, the five stories also demonstrate a diverse set of approaches to leading change in lower and middle income countries…

Inspiring stories of leadership from around the globe

This is a captivating and easy read that strikes a chord in today’s world, where it’s too easy to view countries unlike ours through a lens of judgment. Why haven’t “they” figured it all out yet? De Ferranti tackles that question head-on. He guides the reader through the lives of five incredibly human stories from Africa, Asia, and Latin America. He delves into his subject’s challenges, triumphs, and even their missteps, painting a vivid picture of their individual journeys.

This isn’t your typical geopolitical discourse. What stands out is the focus on their personalities – their strengths, weaknesses, and the sheer human spirit that allowed them to effect change. The book is a deep dive into the personal traits and serendipitous events that shape true change and changemakers. It provokes thought about what is required to make a significant impact in the world…

Refreshing personal perspective on achieving change

I found Five Remarkable Lives most enlightening, and certainly humbling. To be in the company of these remarkable and motivated people was an experience to be remembered.

thought-provoking

This is the kind of book that gets your own mind racing. It’s so good that you start thinking immediately of who you can share it with. The author tells us the stories of five extraordinary people who were remarkable change agents in the worlds in which they operated…mini biographies that read more like a thriller than a quasi academic book. It’s full of inspiration and good story telling. Both in the introduction and the afterword the author analyzes what made it possible for these people to have achieved such success, against great odds. I hope that this book will be well used in high schools and universities, but also that it will find a broad general readership.

I couldn't put it down....

Here is what grabbed me and why I highly recommend this book:

It is a powerful, heartwarming, and inspiring tribute to 5 individuals (from Nigeria, Argentina, India, Zimbabwe, and Peru) for their extraordinary accomplishments in tackling poverty and injustice, thereby enabling struggling populations to build better futures.

The book is based on the author’s personal interactions with each of these individuals over the course of his 50-year career during which he held senior positions at the World Bank, the Brookings Institute, the Rockefeller Foundation, and other organizations.

A Powerful, Heartwarming, and Inspiring Tribute

Why I wrote this book

Several considerations motivated this book. First, the five lives examined in this book challenge us to think from fresh perspectives about our own lives and moment in history. They inspire us at a time when our aspirations for progress seem increasingly at risk. They illuminate for us unfamiliar parts of the world and its problems. They reassure us that our species can come up with individuals who, when all seems lost, will lead us to better destinies and uphold cherished values – promoting democracy, respect for facts, pursuit of the truth, and belief in treating others the way we would like to be treated.

These five life journeys raise thought-provoking questions that have forever captivated our species. What would we do in dire circumstances, terrible quandaries, and life-or-death situations such as they faced? How much of who we are comes from what is in us from the start and how much do we acquire along the way? What accounts for our best and worst tendencies and everything in between? What qualities support us during crises? What makes us sometimes clear-sighted and sometimes blind to what is happening to us and around us? Do we possess the capability and the will to address the threats before us now, including climate disaster and the toxic political, economic, and social problems of our time?

The experiences of any five people do not necessarily provide definitive answers to these questions, but they nourish hope that we can make tomorrow better than today. They help us reflect on our perceptions of cultures distant from our own. They show us that leaders and influencers from faraway places whom we initially tend to Iimagine must be very unlike us are, on closer inspection, not so different after all. They stir us to beat back the “them versus us” in our thinking and welcome in more “we are all just one ‘us’ on this planet”.

The five speak to us not only as separate individuals but also as a group. They give us a window on the worlds they have come from and worked in. Their endeavors and accomplishments enrich our understanding of what constitutes leadership. They highlight what it takes to be an effective decision-maker. They provide insights on international development, the process through which countries raise themselves from poverty to prosperity.

They remind us of the profound changes that lie ahead. Already, Africa, Asia, and Latin America contain roughly 85 percent of the world’s population. That figure will rise to 90 percent in a generation or two. Billions of people who live on less than $20 a day today will be striving in the coming decades to reach the levels attained in the high-income countries. Accommodating those ambitions will be impossible without fundamental economic, political, and social changes that relieve the overtaxing of the planet’s resources. The wake-up call implicit in these trends has yet to be heeded. The five lives can help us understand what will be unfolding around the globe in the coming decades.

****

In some parts of the world, including the high-income countries in North America, Europe, and elsewhere, a stunningly high fraction of the population know little or nothing about the low- and middle-income countries of Africa, Latin America, and Asia. Many smart and capable individuals — doctors, lawyers, business leaders, academics, politicians, and others – in the rich nations that account for 15% of global population have either no reliable knowledge about the other 85% or have been biased by incorrect impressions and misleading stereotypes from the distant past. Uninformed or misinformed voters and their representatives can make misguided choices, seriously impeding progress toward sensible policies for the future of our species and the planet. Addressing that problem was another factor motivating this book. I am hoping that readers will come away with more understanding of people and places they may not have thought much about before – and will be curious to learn more.

***

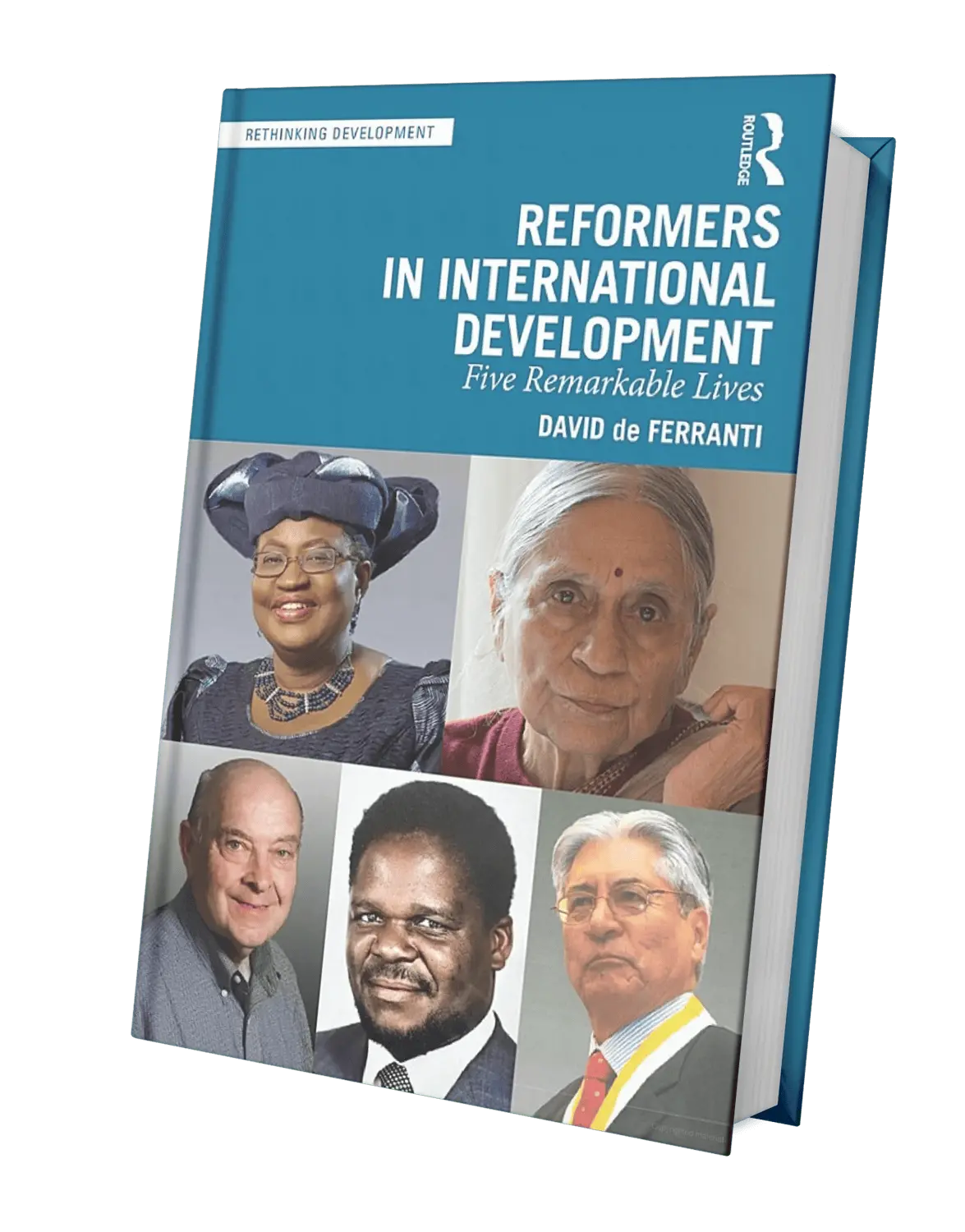

An further motivation was – very simply – that the stories of Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, Domingo Cavallo, Ela Bhatt, Dzingai Mutumbuka, and Adolfo Figueroa are so intrinsically compelling and inspiring that they deserved to be told. Allowing those exceptional lives to disappear unnoticed, as the sands of time bury untold histories, seemed to be an almost criminal act of neglect. Several friends and colleagues argued to me that because I knew all five well, there was a special responsibility for me to write about them.

***

In addition, I wanted to see if these five lives can teach us something new about leadership, decision making, international development, and how evidence is, can, and should be used to make policy choices. These age-old topics are all the more enticing to explore when one digs into the ways that being a leader, decision maker, and force for development is much harder in practice – operating under impossible pressures and working ceaselessly in the trenches – than armchair theorists can ever know. All of that drove me onward.

***

Much of the literature on international development is about what needs to be done – with exhaustive discussion of policies and programs that should be adopted and assessments of how well countries are doing in implementing them. For this book I was interested not in what needs to be done but rather in who gets it done and how they do so. I felt more attention needed to be given to understanding policymakers and the process of policymaking as distinct from the policies themselves, many of which have already been thoroughly studied. Much less has been written about the people who bring about change and lead the messy, arduous task of getting things done. That aspect is clearly no less crucial: without effective leaders and influencers who can push things through – execute, deliver – even the best prognostications about what should be done come to naught.

***

I was intrigued by related broader idea as well. Our species, homo sapiens, prides itself on being the best problem-solvers in the animal kingdom. But we are better at figuring out what should be done than at ensuring our intentions actually do get done. Surgeons, despite their exhaustive training and practice to guarantee that they get everything right, make mistakes. So do airplane pilots, corporate CEOs, mountain climbers, investment advisors, military leaders, politicians, and managers and policymakers of all kinds. The consequences can be disastrous. We are not on track currently to arrest climate change before it drastically deteriorates life as we know it. Growing inequalities, festering ethnic and racial tensions, and tinderboxes of waiting-to-happen conflict and violence are not being resolved. The corona-19 pandemic brought all this home to us once again: much of the world did not do – soon enough – what science clearly showed should be done, resulting in hundreds of thousands of unnecessary deaths, even in the United States, supposedly the home of can-do, get-it-done problem solving.

Getting from should be done to what has been done is at the heart of whether billions of Africans, Asians, and Latin Americans will be able to improve their situations in the decades ahead or not. Will our fragile world succeed at that? There are reasons for hope and causes for concern.

First the hope. In the 75 years between the end of World War II and the outbreak of the covid-19 pandemic, humanity achieved remarkable progress, reducing global poverty and improving living standards for more people at a faster rate than at any other time in our history. By one definition, nearly three quarters of the world’s population were living in extreme destitution in 1950 but that figure had fallen to under 10% right before covid hit. Improvements soared in how long people live, how healthy they are, how much education they get, access to clean water and good nutrition, and more. If we could be so successful then, can we do even better in the decades ahead after finding our feet again after covid?

A second reason for hope Is that even though we have trouble getting from what should be done to what is done, we have been getting better at it. Air travel has gotten safer, not least because pilots have to follow strict protocols, including checklists, that have reduced pilot error. Surgeons’ error rates have fallen, after research found that checklists, teamwork-enhancing measure, and other actions help them too. Learning from experience, we are coming up with better practical guidance and guardrails to help leaders, managers, and policymakers in the public, private, and civil society sectors to lower their risk of making serious mistakes, if they are enlightened enough to listen. Perhaps our ingenuity can help us do fewer things wrong.

Now the causes for concern. The challenges ahead may be an order of magnitude more difficult than what we have overcome in the past. Solving climate change may be tougher than controlling infectious diseases. Political divides and tendencies toward conflict in place of compromise may resist the remedies that worked for us before.

Another concern relates to how good we are at making choices – and how good the choices are that we make. When people in commanding positions, whether in government or other walks of life, make bad decisions, the consequences can have massively adverse impacts, especially in settings where much of the population lives in the grip of poverty. Even making no decision at all can be immensely harmful, delaying an inevitable need to address a serious problem. Seen through that lens, the task of getting done what should be done is in no small part about making decisions and making them right.

Decision-making has been much examined elsewhere. Business schools, public policy programs, and most other kinds of professional training – for doctors, air pilots, investment advisors, finance managers, skilled trades workers, and more – have devoted much attention to studying how people make decisions and what can help them be better at it. Protocols and tools have been developed to help decision-makers find their best options and avoid pitfalls. But advances in those domains have not yet been adopted and adapted sufficiently by decision-makers determining the future of many African, Asian, And Latin American countries. New government officials, leaders in the private and civil society sectors, and international organizations and experts have not yet exhausted the opportunities to learn from others. They are no less keen than their counterparts in other walks of life, I have found, to take on board the best know-how, advice, learning, and tools available worldwide. But the halls of power in their world are a very long way from the theorists and practitioners in the most advanced havens of good decision-making around the globe – and not only in physical distance.

Bridging that divide is a solvable problem. It is a should-be-done that can be done. It is something we humans can accomplish if we put our minds to it. Doing so could contribute to speeding up progress against poverty.

All this got me thinking about what can be learned from people such as Ngozi, Cavallo, Ela-ben, Dzingai, and Adolfo about getting done what should be done. How did they get from intention to results? What worked for them – and what not?

***

The world was in turmoil when I started thinking about writing this book – and that was a further motivator. At the time, the covid-19 pandemic – and the long shadow of its likely economic and social consequences for years to come – were expected to topple decades of progress in reducing poverty, raising living standards, and increasing life expectancy in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. An eventual return to pre-covid-19 normalcy seemed unlikely, and speculation about what a new normal might look like included depressing scenarios about long-term setbacks. The prospect that, amidst the carnage, there might be a silver lining in the form of innovative new ways of doing things (such as more human interaction remotely instead of through so much environmentally damaging and costly travel) seemed alluring but not assured. Hopefully, those prognostications, when viewed ten years hence, will appear unduly pessimistic; predictions of the future often are wrong. But the grim expectations pervading humankind in the early 2020s foresaw some form of serious, lasting, negative impact.

Other factors too were troubling. Populist, nativist political leaders – and the forces and voters who empowered them – seemed to have no time for, and increasingly little understanding of, goals and accomplishments that their parents and grandparents had deemed crucial. In the USA, UK (Brexit), continental Europe, Brazil, Australia, and elsewhere, bedrock institutions seemed suddenly much more vulnerable. Democracy seemed to be stumbling and at risk. Sound economic policies – including sensible trade rules – seemed to be in danger, not least from the right wings of political parties that formerly had staunchly defended them. Core values such as respecting the difference between truth and falsehood seemed to be under attack, and racism seemed to be on the rise again. Over half a century of progress was being dismantled, it appeared. Worried voices were asking whether future generations, as they wrestle with all of this and seek to repair the damage, would have to discover everything anew. Had it become urgent, some are wondering, to record the lessons of recent experience from a more positive time to help future re-inventors find their way more easily?

Still worse, the very idea of progress that my generation grew up with seemed to be disintegrating. My parents lived through the depression of the 1930s and felt the rigors and eventual can-do triumph of resurrecting order and reason after the defeat of Nazism in World War II. In addition, I was the son of an immigrant father who had been ready to sacrifice everything to ensure that his children’s lives would be better than his. With all that came the faith that the steady march of progress is the natural order of things – the inevitable achievement of the ascent of humanity. But now, in the darker days of the early 21st century, the belief that things will always get better, despite periodic setbacks, was looking increasingly naïve. The hope each generation’s advances and lessons learned would become the starting point for the next generation to rise higher began to look quixotic. A closer look at the history of democracy, from ancient Greek times to the present, suggested that it has often not lasted long, only a century or two, before rule by powerful interests reasserts itself. Sensible economic policies seemed prone to be less long-lived than expected, with the mistakes by one set of leaders being repeated by others later. Fairness and respect for basic rights seemed vulnerable to resurgences of simmering racism and hatred.

But buried beneath all this gloom were reasons for hope too, particularly for African, Asian, and Latin American countries and families in them striving to put poverty behind them. Improvements since the 1950s, even with the recent setbacks, still make it possible for today’s young people in those nations to rise much higher and faster than their forebears did. Looking back further in history offers a glimmer of hope as well.[1] Perhaps if we finally get serious about tackling the looming challenges ahead, we can avoid the worst once again.

Those looming challenges are considerable. Among them is the problem that the high-income world has paid little attention – for eons – to the changes afoot across Africa, Asia, and Latin America. In the next few decades, new leaders and influencers from the low-and-middle-income countries will be coming to center stage and will have much more impact than in the past. North America and Europe will be a declining proportion of humankind, slipping down toward a mere 10%. Ignoring the increasing impact of the other 90% will no longer be possible. As the wealthy nations grapple with their headline events of today (Putin’s war, the covid pandemic, the challenge to democracy from political turmoil, the rise of autocracy, and global warming), they will need also to look further out on the horizon and take stock of the approaching tidal wave of change. The stakes are high. Six out of every seven people on the planet now live on less than $20 a day. Those billions will be striving hard to build better futures for themselves and their children – while today’s well-off societies seek to enhance and defend the high standard of living to which they have become accustomed.

All of this was on my mind as the idea for this book was taking shape. The confluence of these threats, opportunities, trends, and tendencies pointed to the importance of current and future leaders and influencers in Africa, Asia, and Latin America – as they spearhead the soon-to-be 90% of the world’s population who live in those countries. What will those movers and shakers be like? What ideas, advice, and objectives will guide them? No one can know for sure. But we can at least take a close look at whatever bits of evidence we have at our disposal. And some of those bits are to be found in the lives of examples we know of already – such as Ngozi, Cavallo, Ela-ben, Dzingai, and Adolfo. Many others too – thousands in fact – but these five are at least a start.

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

[1] Research by archeologists and geneticists posits that the human race dwindled to a tiny number of individuals – perhaps under 15,000 individuals – at some point between 50,000 and 100,000 years ago. One theory attributes our near extinction then to a massive volvanic eruption, one of the largest ever seen on the planet, that occurred about 75,000 years ago and deposited up to six feet of ash across much of the world, snuffing out food sources. Another theory pins the blame on climate changes. Whatever the explanation, the 7.9 billion people alive today are all descendants of that village-size group that was concentrated on the southwest coast of Africa, some experts think. Today, vastly more people enjoy immensely better living standards than those far-back ancestors dreamed possible. While the least well off now are struggling in unacceptably worse conditions than the rest, the fraction of them who are worse off than 75,000 years ago is infinitesimally small. So, however grim the world looks at some moments, humans have implausibly snatched progress from the jaws of “game over” before.

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

Ignoring what is coming – disregarding what it could mean for all regions of the world – remaining deaf to the wake-up call that is beckoning us now – and brushing aside whatever evidence we have from individuals like the five here – would be folly.

***

Finally, bridging the gap between writers and doers was much on my mind when I embarked on this book. People who write about international development issues are sometimes also good at doing the practical work on the ground when trying to bring about effective solutions to problems – but not always. Others who are adept doers are sometimes also strong thinkers and writers – but not always. If I could be granted one wish in regard to the writer-doer spectrum, it would be that each camp do more to appreciate that the other has much to offer. Some doers can be dismissive of the professors who spin ivory tower fantasies and became writers because they are not very good as doers. Some writers can be disdainful of doers who are simply movers of money and pushers of projects insufficiently thoughtful about merits and demerits of the interventions they are supporting. In my experience, there is a tendency – at least in some cases – for each camp to undervalue the other. I’d like to see more of the doers recognize that some of the writers are actually successful doers too and that their research is actually helping the doing notably. And I’d like more writers to acknowledge that some of the doers are actually as good thinkers as the writers are and can contribute much to what the writers write about. Examining the lives of Ngozi, Cavallo, Ela-ben, Dzingai, and Adolfo will, I hope, provide interesting examples of how the two camps can come together more.